Why Newsom’s redistricting fight was a mistake

Editor’s note: This article is an opinion piece and does not necessarily reflect the views of The SELA Sun. It has been edited for length, and updated to include additional news context. An earlier version of this piece appeared on the author’s Substack.

The fact that Gov. Gavin Newsom is casting Texas’s partisan congressional redistricting as the tip of the spear aimed at the heart of American democracy shows, perhaps more than anything else, how desperate he is to be president.

Newsom is getting ahead of attacks soon coming his way. Not from Republicans—he doesn't mind those and probably welcomes them—but in fact from his future competitors for the 2028 Democratic presidential nomination—the likes of, for example, Josh Shapiro, Wes Moore, or Andy Beshear.

That contest begins in earnest right after the event which Newsom would have us think is his all-consuming focus right now: the 2026 midterm battle for control of Congress.

The midterms, says Newsom, will determine the fate of American democracy. If Democrats win, democracy survives.

In service of the sacred charge of defending democracy, Newsom is now asking voters to approve Proposition 50 in the Nov. 4, 2025, election, which will shift control of California’s redistricting process from the state’s independent commission to the Democratic-controlled Legislature.

Of course, Democrats do need to be concerned about which party controls Congress, particularly given the actions of the current president following his loss in 2020. And, to be clear, the Texas redistricting is utterly shameless.

But Newsom's attempt to make himself the focus of attention by exploiting the Texas redistricting ploy is actually detracting from his party’s (already pretty good) chances, not improving them.

For one thing, he obviously knew that he was starting, not ending, a redistricting arms race with other states.

Republicans, led by the autocratic Trump, did just as they were commanded in Texas and have enthusiastically followed their dear leader’s wishes in other red states as well.

Missouri’s governor has already signed a new congressional map in the hopes of netting Republicans another seat. GOP lawmakers in Florida, Indiana and Kansas are forwarding similar moves, while Republican-controlled Ohio is already set for mid-decade redistricting. In North Carolina, Republicans passed a new congressional map this week that is expected to add another GOP-leaning seat in next year’s midterms.

True, we see Democratic-controlled Maryland eyeing its own round of counter-counter-counter redistricting while some Democrats in Illinois have been hesitant to advance a redistricting scheme for the very reasons I’ll explain shortly (Democrats in New York have proposed new maps that, if approved, would not take effect until after 2026).

But there are just more states with Republicans in control of their state’s redistricting process, if you play this thing out.

There are in fact 162 congressional seats in Republican-controlled states versus 51 seats in states where Democrats control the process (this includes Nebraska, whose legislature is nominally nonpartisan but which leans heavily Republican). The remaining seats represent states where the parties split control of the two houses of their legislature or have an independent redistricting commission, according to August 2025 data from the National Conference of State Legislatures and Loyola Law School’s All About Redistricting project.

So even if you move California from the independent commission column to the Democrat-controlled process column, as Newsom seeks to do with Prop. 50, you still have Democrats controlling the process for 103 seats versus the Republicans controlling 162 seats.

If you’re a Democrat, how do you like those odds?

Funny how Newsom neglects to mention this particular math as he touts himself as the leader of the Resistance. If he's its head honcho, the Resistance forgot to add strategist to the job description.

And it’s not just this simple math Newsom seems either not to comprehend (or pretends not to comprehend) as he leads the charge in this redistricting war between the states. It's also the nature of redistricting itself.

The fact is, squeezing extra seats for one party or another out of extreme gerrymandering only works in a status quo election scenario. Basically, if you expect to keep the seats you already have, then the redistricting party benefits from their own gerrymander.

But if voters move your way in a landslide, not only needn’t the more popular party gerrymander its way to a win—and not only can’t the other side’s gerrymandering stop it—but the scheme can actually blow up in its face, making the result worse.

That's because gerrymandering is all about drawing arms and tendrils from competitive districts into not-so-competitive districts.

Say Party X expects to win District 1 by 60–40 and lose District 2 by 45–55. By redrawing the map, it can pull voters from District 1 into District 2, siphoning off “wasted” votes from the lopsided district. Shift about 7% of reliable Party X voters this way and, all else equal, District 1 drops to 53–47 while District 2 flips to 52–48—giving Party X both seats.

But what if all else isn't equal?

What if Party Y performs 3.5 percentage points better on average in this election than it did in the last election?

Guess what, Party Y—thanks to Party X's redistricting scheme—has just won two seats, not just the seat it expected to win, but also the other seat which used to be a safe Party X seat!

This is the kind of risk-reward analysis that one must do if one is serious about the implications of redistricting. It also demonstrates the potentially countervailing forces at play that limit the effects of gerrymandering from being the 10-foot-tall boogeyman it's sometimes made out to be, to being a bit more of a paper tiger.

I can easily recall two wave elections deemed “impossible” under gerrymandered maps. In both 2006 and 2018, the fact that Republicans controlled redistricting in so many states meant that Democrats could never retake control of Congress... until they did.

They won because they were more popular than the unpopular Republican presidents at the time. Not only did the gerrymandered castle walls of Republican congressional majorities fail, they likely backfired, costing Republicans extra seats.

However, if one is simply trying to exploit redistricting for short-term political gain, like Newsom, these sorts of mathematical and historical details get left by the wayside in the headlong push towards TV cameras and social media tit-for-tat battles (in Newsom’s case, pathetically converting his official Office of Governor X account into a gross, all-caps attempt at satire, which just highlights Trump’s seeming ability to pull everyone down to his level in every imaginable way).

The reality of the situation is that, regardless of all the rhetoric and maneuvering right now, the 2026 midterm is very likely, if history is any guide at all, to be enough of a Democratic wave favor for them to retake the House, if not the Senate, as well. The out-of-presidential power party tends to pick up, on average, 28 seats in the midterm election.

Democrats only need to pick up three seats to take the house.

There is an almost inevitable pendulum swing between the two parties, with buyer's remorse setting in for the president's party by the time of the two-year itch, especially when that party has control of both Congress and the White House.

You don't even need Trump’s tariffs, inflation, a weakening economy, constant attacks on the checks and balances of democracy, and mass immigration raids to cause that natural unpopularity to occur at the next midterm, believe it or not.

All the makings of a wave election were already there.

Except for one thing: The Democratic Party is not as popular as it arguably should be right now.

It's still very early to forecast the midterm, but right now the RealClearPolitics 'generic ballot‘ has Democrats up less than three points on Republicans, 45.9% to 43.3%. That's after an aborted conquest of Greenland, a 10% tariff on that island with all the penguins, and restaurant and grocery prices still ridiculously high.

One can imagine that close margin is perhaps what motivated Texas’s redistricting in the first place. Team Trump hoped that if they could just tip the scales back in their favor a bit, they could avoid all the subpoenas and impeachments a Democratic House will surely have in store for them during the second half of Trump II.

Maybe the early polling convinced them it was worth the risk to try to squeeze a few more Republican seats out of Texas while diluting the margin of safety in other Republican seats, thereby keeping a threadbare House majority.

Or perhaps they are equally as ignorant of the risk-reward tradeoffs of redistricting geometry as the average California governor or television commentator appears to be.

The lesson of all this should be clear to both sides: Actually focus on trying to win the next election by trying to win the next election!

Elections are won by relating to voters’ real concerns and presenting them with a positive agenda they agree with and believe is possible. This isn’t rocket science.

It’s just that parties get constrained by serving their own extremist bases, tangling themselves up like pretzels.

And figures like Newsom—much like Trump—see the base play as their best path to winning presidential primaries. Just as Trump relied on rank-and-file fervor in all three of his nomination victories, Newsom hopes to convert the current Democratic disaffection into a sort of contrived elation over district maps.

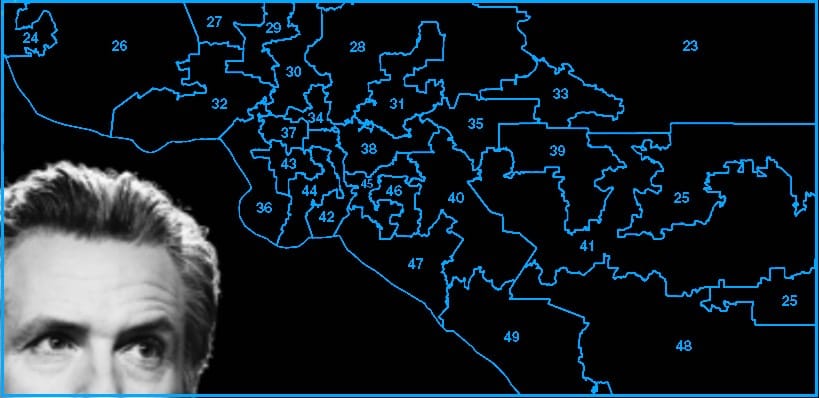

And that’s ironic, since Newsom’s redistricting plan also strikes at the spiritual heart of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in a place like Southeast LA County. He basically sees congressional districts as banks of Democratic voters to be freely redistributed into more purple-to-red territory to the east, as needed.

That goes against the fundamental VRA-related principles impressed upon our Citizens Redistricting Commission, who were told their goal was not only to draw districts as compact (armless and tendril-less and tentacle-less) as possible, but also to keep “communities of interest” together.

The current commission took those values to heart and achieved a remarkable feat: Its maps avoided even a single VRA-based court challenge of the kind seen in so many other states. It remains one of the few institutions in California with genuine bipartisan public support and respect.

Another irony is that Newsom has employed the very ‘stop the steal’ rhetoric of Donald Trump in his redistricting push. Texas isn’t just pushing the bounds, to hear Newsom describe it. They are “rigging” the election. Gee, who was the last guy who bellowed about an election being rigged? I’m trying to remember his name.

If a Democrat wins the White House in ’28 and suffers a typically bad midterm in 2030, Democrats in Congress will be fighting that battle with these gerrymandered lines—another misleading claim is that the California gerrymander would be “temporary” when in fact, if Prop. 50 passes, the new lines will remain in effect in ’26, ’28, and ’30, until they would have been changed anyway in 2031, following the results of the 2030 census.

That means that, just as the gerrymander in Texas may backfire next year, the California counter-gerrymander may backfire in 2030, making midterm losses then even worse.

But Newsom will have long since exited the Sacramento stage by then, either having achieved his ultimate goal in life of becoming president or having jetted back to his mansion and wineries.

Ian Patton is the executive director of the Long Beach Reform Coalition, a nonpartisan group that advocates for good-government reforms. He is also a political consultant and has lived in Long Beach's Bixby Knolls neighborhood longer than the internet has existed. Find more of his commentary at calhtsconsult.substack.com.